Understanding Burnout in Today's Workplace

Burnout has gone from being a workplace buzzword to a genuine occupational health issue, yet plenty of workers still aren't sure when they've crossed the line from being exhausted after a difficult week to actual burnout. Knowing the difference matters—not just for your own wellbeing, but for your workplace too.

What Burnout Actually Is

Burnout isn't just feeling tired after a demanding fortnight. The World Health Organization officially recognised burnout in 2019 as an occupational phenomenon with three main features: complete exhaustion, growing cynicism about your job, and feeling like you're getting less effective at work.

“Unlike normal stress that goes away after a restful weekend, burnout is a chronic state where you’re completely out of sync with your work. It usually builds up slowly over months or years.”

What makes burnout particularly difficult is how gradually it creeps up. Most people don't wake up one morning in full burnout mode. Instead, they experience a slow erosion of their enthusiasm, energy, and effectiveness. The keen employee who used to volunteer for projects becomes someone who just does the bare minimum. The caring professional who prided themselves on going above and beyond starts feeling emotionally drained by routine interactions. These changes signal something more significant than just a rough patch.

It's Not Just About Being Busy

While too much work definitely contributes to burnout, research shows it's more complicated than that. Burnout emerges from a dynamic interplay between person and workplace, but contemporary evidence suggests that, on average, work conditions and person–job fit are more actionable levers than “individual weakness,” with personality and mental health vulnerabilities powerfully shaping who is most at risk. (Schaufeil et al 2001)

Work conditions explain a substantial proportion of variance in burnout, particularly the exhaustion and cynicism components.

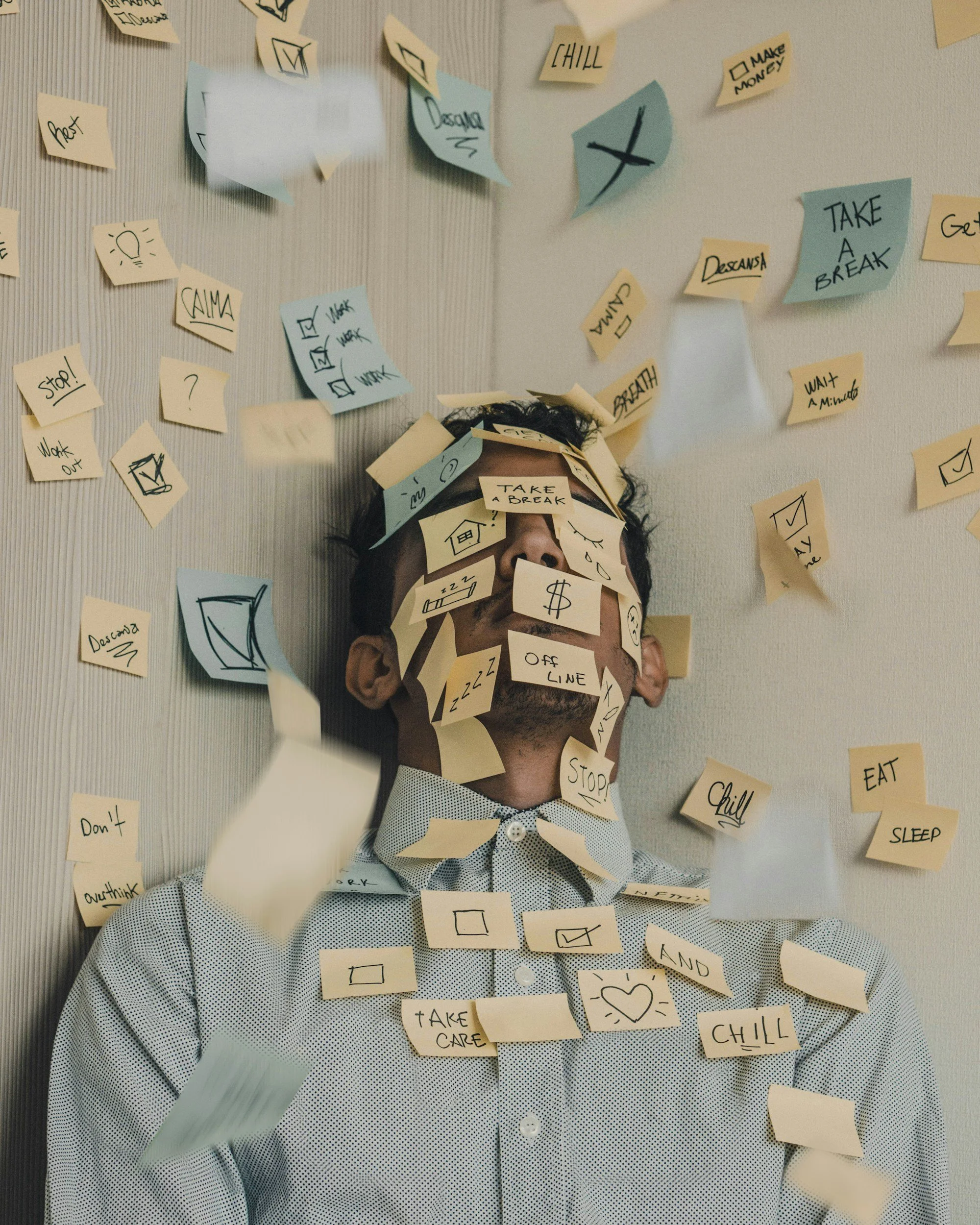

Stressed at work

Unrealistic demands play a part, but burnout typically comes from a combination of workplace factors. When a person has no control over the work they do, no say in decisions affecting their job, no flexibility in how they do their tasks, and no autonomy over managing their time, they can end up feeling like a passive bystander rather than someone actively engaged in their work.

Not getting recognised for their efforts is another major factor. We all need to feel like what we do matters, that someone notices when we put in effort and commitment. When good work goes unnoticed—or worse, when only the problems get attention— people can become disillusioned. This slowly disconnects them from any sense of purpose in their role.

Workplace relationships are a significant contributor to workplace health. Wellness incompatible work environments which are full of conflict, lack support, or create isolation, fast-track burnout. On the flip side, solid relationships with colleagues and supportive leadership can protect people from burnout even in demanding roles. This explains why two people doing similar jobs in different teams can have completely different experiences—the environment around the work often matters just as much as the work itself.

“Solid relationships with colleagues and supportive leadership can protect people from burnout even in demanding roles”

Finally, when personal values are in contrast to workplace standards a particular kind of exhaustion can be experienced. When a person has to regularly deal with organisational priorities that clash with what they believe in, or feel forced to do work they find meaningless— they can experience a sense of erosion of self-worth and this fuels burnout.

Personal factors also play a role

Burnout isn’t caused by work conditions alone. Who we are, what we’ve been through, and what’s happening in our lives outside of work also make a difference.

Research shows that some personality traits are linked to a higher risk of burnout. For example, people who tend to worry a lot, feel emotions intensely, or expect the worst are more likely to feel emotionally exhausted and overwhelmed at work. In fact, some studies suggest that personality can explain a part of why some people burn out more than others, sometimes even more than workload or job pressure.

Other traits matter too. People who are less outgoing, less organised, or who doubt their own ability to cope may be more likely to feel disengaged, cynical, or ineffective at work. Over time, this can feed a sense of “what’s the point?” and reduce feelings of achievement.

“Mental health is important.”

People who are already experiencing depression, anxiety, or high levels of psychological distress are more vulnerable to burnout. In some workplaces, mental health difficulties and poor organisational structure together are the strongest predictors of both burnout and reduced job satisfaction.

Finally, life outside of work counts. Ongoing stress at home, financial insecurity, caring responsibilities, or feeling unsafe or unstable in daily life can significantly increase burnout risk—especially when work stress spills over into personal time.

Overall, the evidence suggests burnout is most likely when work pressure, personality style, mental health, and life stress all interact. It’s not a personal failing—it’s a complex mix of demands and vulnerabilities coming together.

Spotting the Warning Signs

Burn out can lead to disrupted sleep and emotional exhaustion

Physical exhaustion shows up as constant tiredness that sleep doesn't fix. This can lead to getting sick more often as stress weakens the immune system. Headaches, muscle tension, digestive issues, and sleep problems often come with burnout—these are the body's way of protesting.

Emotionally feeling drained, flat, or increasingly cranky and cynical. People may find themselves becoming detached from work that once interested them, feeling numb rather than engaged. Many people experiencing burnout describe feeling like they're just going through the motions, doing their job mechanically without any real connection to the work or the people around them.

Mentally, burnout impairs concentration, decision-making, and memory. Tasks that once felt straightforward become confusing or overwhelming. This can lead to uncharacteristic mistakes, forgetting important details, or struggling to focus during meetings. This brain fog isn't laziness or incompetence—it's the brain's response to prolonged stress.

Behaviour-wise, burnout can often lead to pulling back from responsibilities, lower productivity, and increased absenteeism or just showing up physically but mentally checking out. Other behaviour can also occur, such as arriving late to work, leaving early, or taking more sick days. Producing work that meets minimum standards but lacks their usual quality or creativity can be another sign of impending burnout.

Breaking the Cycle

Getting past burnout needs both individual action and workplace changes. On an individual level, establishing clear boundaries becomes essential. This means defining realistic limits on work hours, learning to say no to additional commitments when already overextended, and protecting time for recovery activities. Many high-performing professionals struggle with boundaries because their identity became intertwined with being the person who always says “yes”, who always delivers, who never lets anyone down. Redefining what responsible professionalism looks like—recognising that sustainable performance requires self-protection—represents a crucial mindset shift.

Reconnecting with meaning helps combat the cynicism dimension of burnout. This might involve reframing the work to focus on aspects that align with personal values, seeking opportunities for more meaningful projects, or finding purpose outside work that provides fulfillment the job no longer delivers. Not every job needs to be a person’s passion, but we do need sources of meaning and satisfaction in your life overall.

Building support networks fights isolation and gives emotional backup. This includes cultivating relationships with colleagues who understand the work challenges, maintaining connections with friends and family outside work, and potentially seeking professional support through counselling or coaching. Talking about burnout often helps people realise they're not alone in their struggles and can surface solutions they hadn't considered.

Organisations need to step up too. This means honestly looking at whether workloads are reasonable, creating ways for employees to have some say and control, recognising people's contributions properly, building psychologically safe teams, and having leadership model healthy work-life balance. Burnout prevention isn't just about individual resilience—it's about how workplaces are designed and run.

When to Get Help

If you're experiencing persistent symptoms that interfere with daily functioning professional support is a good place to start. Behaviours such as:

using alcohol or other substances to cope with work stress,

gambling, pornography or shopping are other behaviours people may also use to cope.

If you're having thoughts of self-harm, or

if your relationships are suffering significantly due to work-related exhaustion and irritability,

these are signs to seek professional help. Speaking with a counsellor or psychologist can provide you with support and practical strategies for managing workplace stress and burnout.

“Sometimes an outside perspective helps identify patterns and solutions that aren’t visible from inside the situation.”

Moving Forward

Understanding burnout is the first step toward dealing with it. Whether you're recognising these patterns in yourself or you're a leader seeing them in your team, acknowledging the reality of burnout creates the possibility for change. Sustainable performance isn't about pushing through exhaustion—it's about creating conditions where people can actually thrive long-term. In today's demanding workplaces, this isn't optional; it's essential for both people's wellbeing and organisational success.

FOR A SUMMARY OF THIS BLOG PLEASE DOWNLOAD OUR NEWSLETTER ON BURNOUT.

-

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422.[wilmarschaufeli]

Schaufeli, W. B. (2009). Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Development International, 14(3), 204–220.[wilmarschaufeli]

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding burnout: New models. In Job burnout: New directions in research and practice (updated insights in later reviews).pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih+1

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands–resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328.[pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih]

Bianchi, R., Verkuilen, J., Verkuilen, J., Schonfeld, I. S., Hakanen, J. J., Jansson-Fröjmark, M., & Laurent, E. (2021). Is burnout primarily linked to work-situated factors? A relative weight analytic study. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 623912.pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih+2

Bianchi, R., Schonfeld, I. S., & Laurent, E. (2018). Burnout is more strongly linked to neuroticism than to work-contextualized factors. Psychiatry Research, 270, 901–905.sciencedirect+1

Bianchi, R., & Schonfeld, I. S. (2022). Burnout: A review of theory and measurement. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 865311.[pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih]

Zhang, X., et al. (2023). Big Five model personality traits and job burnout: A systematic review. BMC Psychology, 11, 53.[pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih]

Nielsen, M. B., et al. (2017). Work environment factors and burnout: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 43(6), 436–449.[pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih]

Schaufeli, W. B., & Salanova, M. (2014). Burnout, boredom and engagement in the workplace. In M. C. W. Peeters, J. de Jonge, & T. W. Taris (Eds.), An introduction to contemporary work psychology (pp. 293–320). Wiley-Blackwell.[wilmarschaufeli]

Mayo Clinic Staff. (2023). Job burnout: How to spot it and take action. Mayo Clinic.[mayoclinic]

-

DISCLAIMER: The information provided in these blog posts is intended for general educational and informational purposes only. It is not a substitute for professional psychological assessment, diagnosis, or treatment. Individuals should not rely upon this content as professional advice, nor should it be used to guide or replace clinical decision-making.

Although all content is written by qualified mental-health professionals and draws upon contemporary psychological research and recognised frameworks (e.g., APS Code of Ethics, 2014; AHPRA Guidelines for Advertising Regulated Health Services, 2020), the material may not apply to every person or circumstance. Psychological needs are highly individual, and effective care requires a personalised clinical assessment. Reading these posts does not create a therapeutic relationship with Ashcliffe Psychology or any of its clinicians. In an emergency, call 000 or attend your nearest emergency department. If you are experiencing distress, concerned about your mental health, or require support, please contact a registered health professional. Ashcliffe Psychology makes no warranty regarding the accuracy, completeness, or applicability of the content at any point in time. Blog posts may refer to sensitive topics and may be updated or removed as needed to ensure compliance with professional and regulatory standards.

Use of Artificial Intelligence: Ashcliffe Psychology may utilise artificial intelligence (AI) tools in limited circumstances to support content development. Any material generated or informed by AI undergoes review by qualified clinicians to ensure accuracy, legitimacy, and alignment with professional, ethical, and regulatory requirements before publication.